By Nathan Kiwere

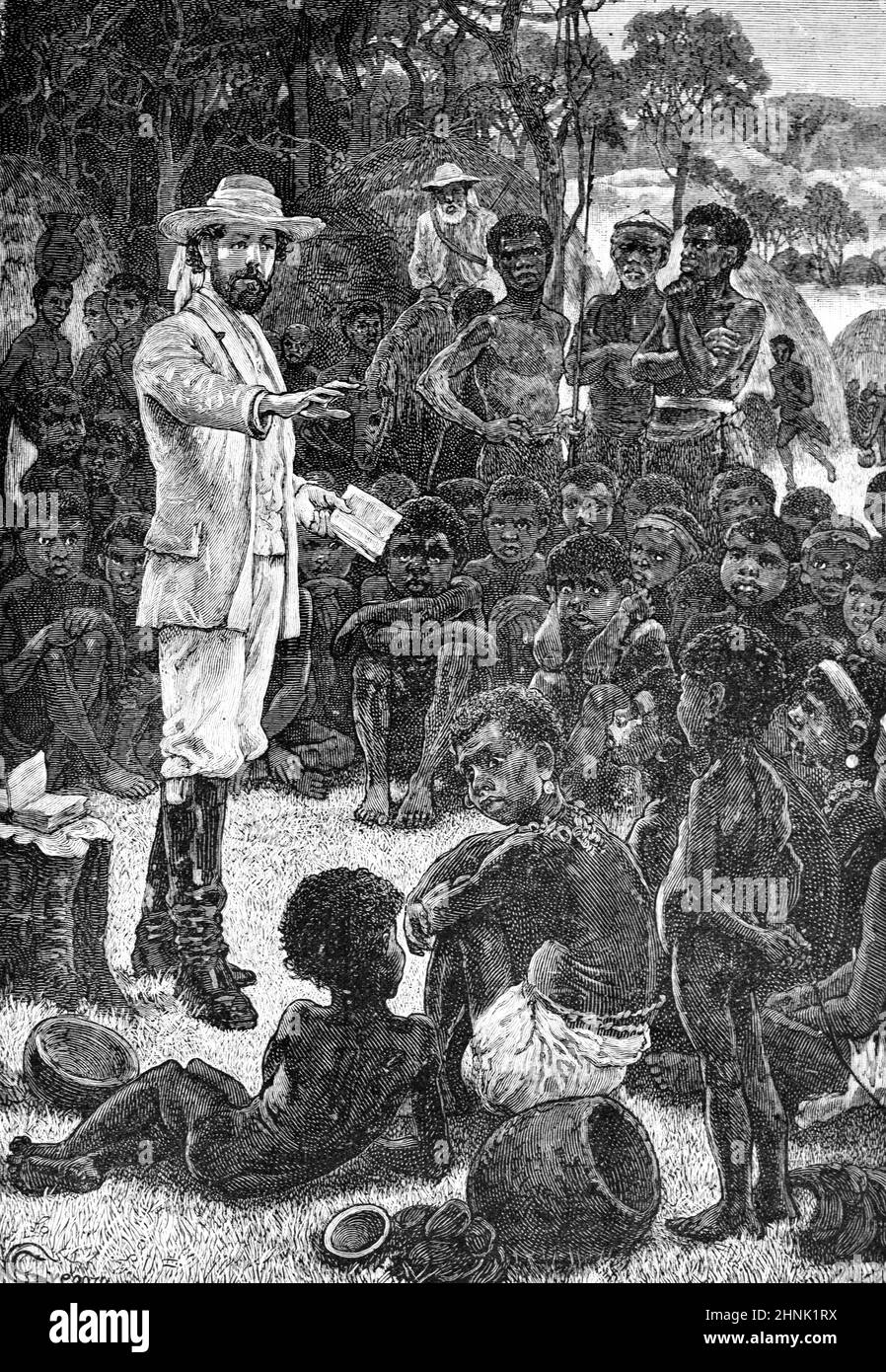

When Christianity first set foot on African soil, it was greeted with amazement as well as suspicion. The message of one almighty God who had sent His Son to redeem humankind stood headlong against the rich spiritual tapestry that had been guiding African people for centuries. These native systems were not merely religious—they were the heartbeat of African identity, regulating social order, morality, and communal harmony. It was thus not merely that the missionaries had arrived to introduce a new faith; they unwittingly introduced an insidious revolution of culture, power, and worldview.

The early contacts between the missionaries and traditional leaders in most of Africa were spectra of cross-cultural misunderstanding. Missionaries understood African religious rituals—worshiping ancestors, divination, initiation rites, and group festivities—to be pagan and devilish. Converts were forced to abandon old practices, forsake their names, and even change their dressing. This placed a whole generation of Africans in between two worlds: the sacred tradition of their ancestors and the compelling message of salvation through Christ.

One can envision scenarios like an African convert in the early 1900s—namely, a young man from a royal family—caught between the loyalty of his clan and his new Christian faith. He could claim Sundays in church, clad in a formal European suit, yet come home to elders awaiting him to pour libation for his ancestors. His personal strife reflected that of a continent in upheaval, unsure as to whether to retain or relinquish its spiritual heritage.

But amidst this dislocation, something wonderful began to happen. Slowly, African Christianity stopped being a imported creed. It began to live with an African breath. The gospel took root in native tongues, hymns were sung to drums and xylophones, and church services began to acquire the rhythm and energy of African life. Where the Christian message was formerly contained within colonial authority, now it was conveyed in proverbs, dance, and businesslike worship—the center of African culture.

Descriptively, one can visualize an active Sunday church service in a village church: women in colorful cloth, men clapping to the drums, and children dancing with joy as a choir leads the introduction of a hymn sung in a local dialect. The sermon can refer to biblical parables and African folk stories side by side, drawing wisdom from Jerusalem and the village hearth. This is Christianity, yes—but rich and unmistakably African.

This adaptation was a turning point. Christianity was no longer the African culture’s enemy but a means by which it could be revitalized. Concepts of community from ancient times, respect for elders, and shared burden merged with Christian notions of love, forgiveness, and stewardship. Simultaneously, offensive practices—sacrificial rites, for instance, or witchcraft, or the subjection of women—lost gradually their moral justification in the light of the Word of God. The gospel was both reflector and purifier of African tradition.

The rise of Christian leadership from within the continent also accelerated this development. They were not successors to the missionary heritage but visionaries who interpreted the Bible in African perspectives. They preached in their own languages, composed hymns that used the traditional melodies, and established independent churches that celebrated African spirituality within the context of Christianity. Among them were prophets, healers, and reformers whose ministries drew thousands with spiritual and social liberation.

By their ministry, African Christianity was revitalized—shaped not imitated but developed in the African soil of experience. The African church focused on nation-building, education, healthcare, and social justice, and became a force of moral righteousness in public life. From prayer huts to cathedrals, from rural revivals to urban crusades, the message of Christ was proclaimed not as colonial legacy but as native belief.

Today, the history of Christianity and African culture is no longer one of conflict. It is one of dialogue, blending, and ongoing change. The African Christian no longer has to choose between the Bible and the drum; he welcomes both, singing the praises of God together with the heartbeat of his people.

Finally, Africa did not simply adopt Christianity but reinterpreted it. The religion that arrived dressed in foreign garments today wears African attire. The God previously discussed in strange tongues now speaks natively in African proverbial language. The cross once considered a symbol of triumph today heralds redemption, reminding us that the message, once understood, transcends cultural fences but never destroys them.

African Christianity in its mature form is a living testament that the God Spirit is not tied by geography, ethnicity, or ritual. It exists wherever hearts are open and cultures are willing to be changed. From the dry villages of the Sahel to the city centers of Southern Africa, the Church continues to sing its song of salvation—a hymn of faith that is older than the continent but ever new in its expression.

Leave a Reply